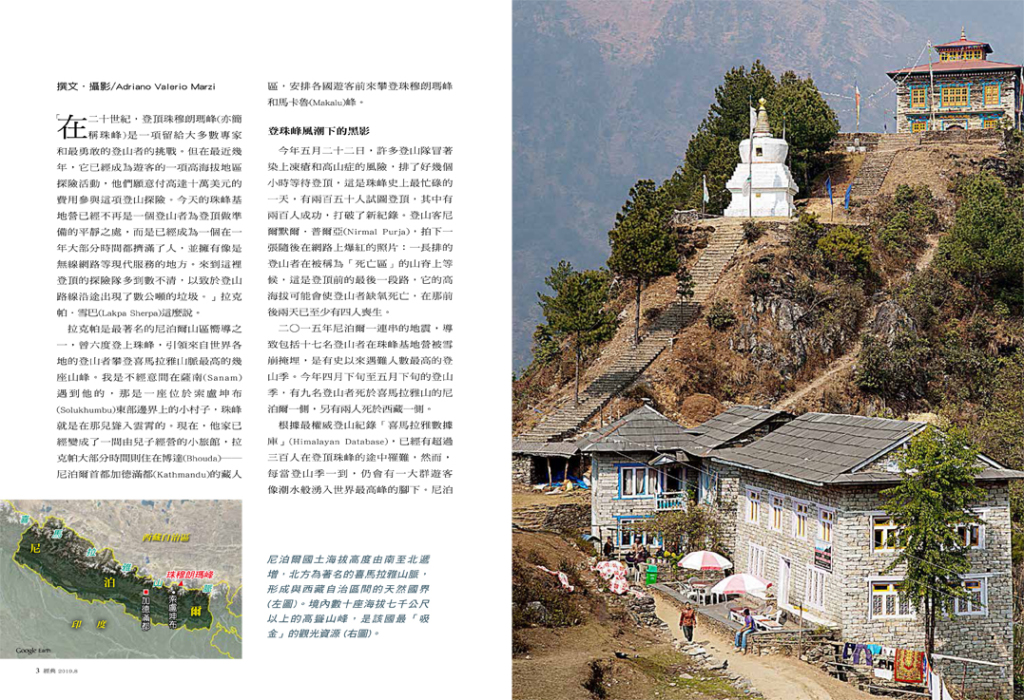

“In the XXth century, reaching the Everest peak was a challenge reserved to the most expert and bravest climbers. In recent years it has turned to an adventure for high-altitude tourists ready to pay as much as 100,000 dollars to be part of an expedition. Today the Everest Base Camp is not anymore a peaceful spot where climbers can prepare themselves for the peak. It has become a place crowded most part of the year, equipped with all modern comforts including wifi connection. Expeditions bound to the mountain top are so numerous that tons of garbage are to be found on the way”. Lakpa Sherpa is one of the most famous Nepali mountain-guide, who climbed Mount Everest six times and guided climbers from all over the world on the top of some of the highest Himalayan peaks. I meet him by chance in Sanam, his native village, on the eastern border of Solukhumbu, the region where Mount Everest rises. Today his native home has turned to a guest-house managed by one of his sons, while Lakpa spends most of the year in Bhouda, the Tibetan district of Kathmandu, where he organizes expeditions on Everest and Makalu for tourists coming from United States and Australia. A prominent business in Nepal.

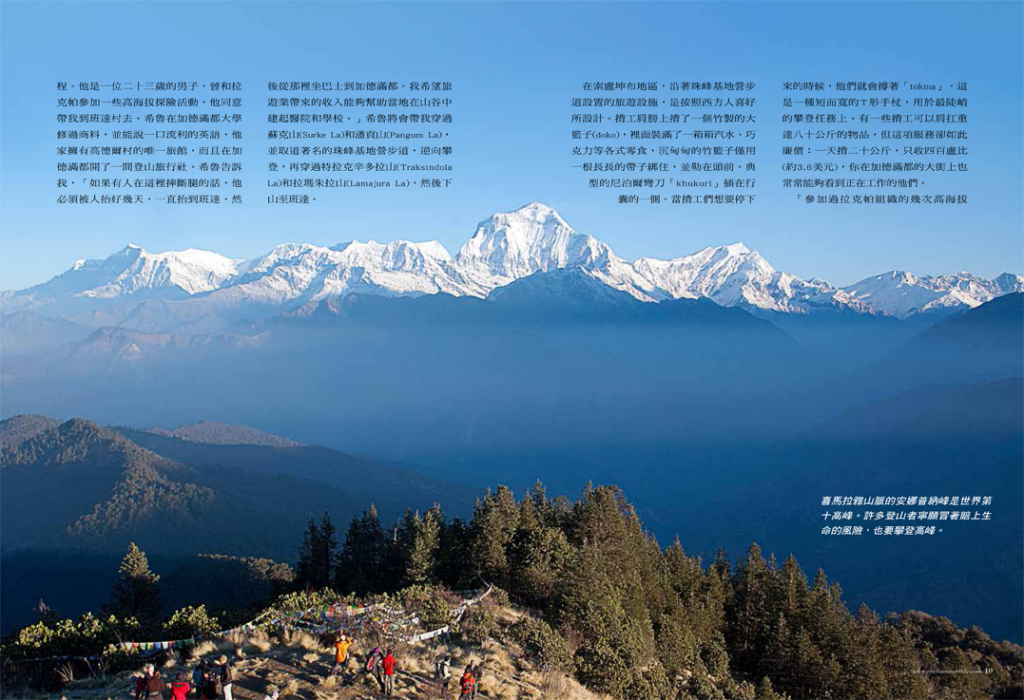

According with Himalayan Database, the most authoritative records of climbs edited by journalist Elizabeth Hawley, more than 300 people have died trying to reach the Everest peak. Nevertheless, every new climbing season a horde of high-altitude tourists flood on the highest mountain of the world. Nepali government, which cashes in 11,000 dollars from every tourist wishing to rise the Everest, in 2019 granted a record number of 381 expedition permits. Most of the climbers were inexperienced people, thus increasing the risks of deadly accidents. On May 22nd, many expedition teams had to line up for hours to reach the peak, risking frostbite and altitude sickness: it turned to be the busiest day in Everest history, with 250 people trying to reach the peak, 200 of them successfully. A new record. The picture took by Nirmal Purja – a Gurkha (Indian) mountaineer, who is attempting to climb all 14 mountains above 8,000 meters in just 7 mounths – became viral: a long line of climbers waiting on a ridge in the so-called “death zone”, the final climbing stretch where altitude can be fatal cause of oxygen lack. At the end, 2019 has been the deadliest climbing season since 2015 – when a series of earthquake killed thousands of Nepali people, including 17 climbers buried under an avalanche at the Everest Base Camp – with 9 mountaineers dead on the Nepali side of the mountain and 2 on the Tibetan side.

The main victim of this crazy circus are “sherpas”, the porters whose support is vital for every single mountain expedition. They are in charge of preparing the way along which climbers will proceed, fixing security ropes and stairs, installing the camp, carrying food and equipment (like the heavy oxygen cylinders which would avoid their rich customers the risk of cerebral or pulmonary edema). To accomplish these tasks they have to go up and down along the most dangerous sections of the climbing way. As a result, they account for one third of the people died in the Everest climbing history. Seven of them were buried by an avalanche during the famous George Mellory expedition in 1922, the first (unsuccessful) attempt to reach the highest peak of the world. Sherpa job has the highest mortality rate (1.2%) for workers: the percentage of porters who have died working in the Everest climbing business since 2004 up today is 12 times higher than death rate among soldiers fighting in Iraq war between 2003 and 2007.

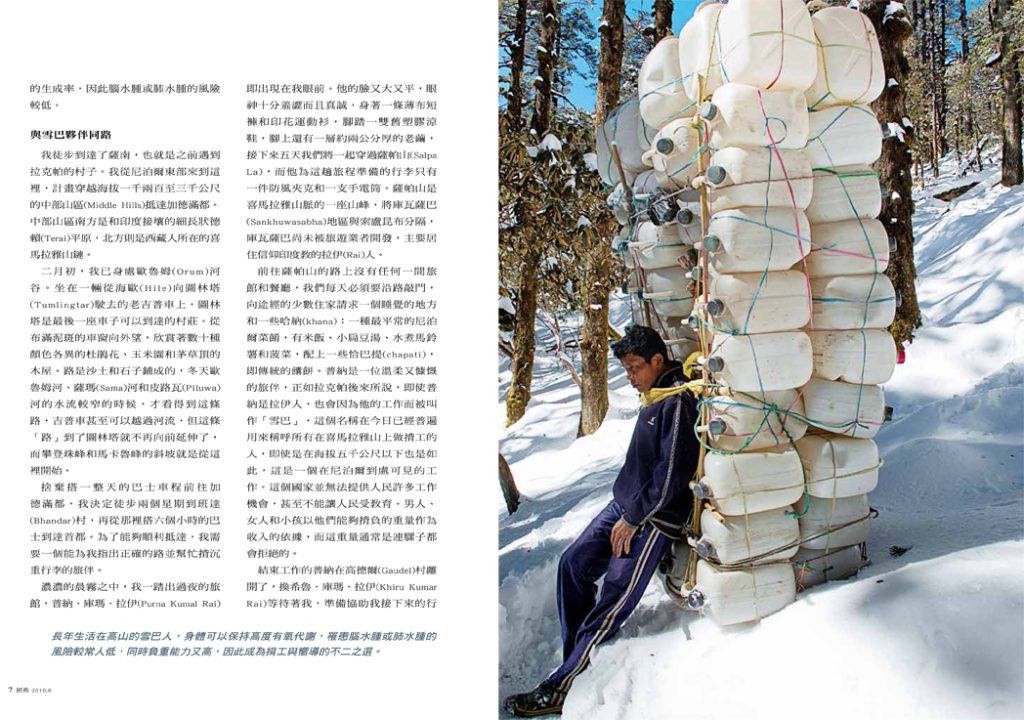

Sherpas, the “Eastern people” – in the Tibetan language pa means “people” and sher or shar means “East” – are the main group inhabiting Solukhumbu, the region where Mount Everest rises. They started to settle in this area during the XVth century, having left the Kham province of Tibet and made it through Nang-pa La (an Himalaya Pass at 5,716 meters altitude), to get away from Mongols invasion. A migratory flow which had a second wave at the half of last Century following Chinese occupation of Tibet. Prior to the development of the high-altitude tourism business, sherpa people had never showed interest in reaching mountain peaks. In their native language there’s not even a word for “mountain top”. Every single mountain is named after the godhead which is said to inhabit it. As an example, Mount Everest is named Sagarmatha, “the abode of Mother Earth”. Tenzin Norgay, the porter who in 1953 guided Edmund Hillary up to Mount Everest’s top for the very first time, has thrown limelight upon them. But sherpas’ celebrity is mainly due to their extraordinary capacities on the heights: they are able to climb for days carrying up to 80 kilos on their shoulders. According with researches carried out by several scientists (Rasmus Nielsen, Paolo Cerretelli, Norman Heglund), sherpas’ body can keep a high aerobic power without increasing the production of red blood cells, thus reducing the risk of cerebral or pulmonary edema.

I reach Sanam, the village where I met Lakpa, by foot. Coming from Eastern Nepal, my plan is to get to Kathmandu crossing the “Middle Hills” – the area between the “Terai”, the thin stripe of plain bordering with India, and the Himalayan mountain chain, which borders with the Tibetan occupied territories. At the beginning of February I find myself in the Orum river valley, on board of an old jeep moving from Hile to Tumlingtar, the last village which can be reached by car. Outside of the muddy window, I can admire rhododendrons of tens different colours, corn terraces plantations, wood huts with thatched roofs. Made by sand and stones, the way to Tumlin’ is viable just during the winter, when Orum, Sama and Piluwa rivers are smaller and the few jeeps which work on this route can cross the rivers flows. The “road” finishes at Tumlin’, where the footpaths which climb Everest and Makalu slopes start. Avoiding a full day bus journey to Kathmandu, I’ll walk two weeks to reach Bhandar village and over there I’ll get on a 6-hours bus to the capital city. A task for which I need the help of a companion to show me the right way and help me carry around my heavy baggage.

Purna Kumal Rai appears in the thick morning fog. He’s waiting for me in front of the guest-house where I spent the night. His face is large and flattened, his eyes are shy and heartfelt. He wears a light cloth shorts and a flayed jersey. Under his foots, he has a 2 centimeters high corn and a pair of old plastic sandals. A windcheater and a torch are the only extra-baggage he’ll bring with him on our five days journey through Salpa La – the Himalayan Pass which divides Sankhuwasabha, a region not yet reached by tourism and inhabited mainly by Rai people of hindu religion, from Solukhumbu.

On the way to Salpa La, there are no guest-houses and restaurants. Every day we have to knock at the door of the few houses we find along the footpath asking for shelter and khana, the most common Nepali dish, made of rice, lentils soup, boiled potatoes and spinaches, served with some chapati, the traditional bread. Purna is a gentle and generous companion. As Lakpa will explain me later, even if he’s a Rai, Purna is named “sherpa” because of his job. Today the name is commonly used to refer to all the porters operating on Himalaya, even below 5,000 meters level. A job prevalent in Nepal, a country which does not offer many opportunities even to educated people. Men, women and children paid according to the weight they are ready to carry. Often more than that even a mule would reject.

Purna takes leave at Gaudel village, where Khiru Kumar Rai is waiting for me. This 23 years-old man, who joined Lakpa in some of his high-altitude expeditions, accepted to help me reach Bhandar. Khiru studies commerce at Kathmandu University and speaks a fluent english. His family is owner of the only guest-house in Gaudel and they are opening a trekking agency in Kathmandu. “If someone fractures his leg here, he must be carried on shoulders for days as far as Bhandar – he tells me – and then from there loaded on a bus bound to Khatmandu. I wish tourism may contribute to building hospitals and schools in these valleys”. Khiru will guide me trough Surke La and Pangum La, the pass connecting with the Everest Base Camp trek. Once over there, we’ll take the famous Himalayan trekking route in the opposite direction, passing through Traksindola La and Lamajura La and finally walking down to Bhandar.

In Solukhumbu region, along the Everest Base Camp trek, tourist facilities are supplied according to Western tastes. Packing cases full of soft beverages, chocolates and any sort of snacks emerge from the doko placed on porters’ shoulders, fastened to their forehead by a long band. The typical Nepali curved blade knife, the khukuri, is fastened by the side of the load. When porters need make a halt they lean against their tokma, a squat T-shaped stick that they use as well in the steepest climbs. Some porters can carry on their shoulders up to 80 kilos. The service they offer is so cheap – 400 rupees (little more than 3 dollars) a day for 20 kilos load – that you can see them often working in Kathmandu streets too.

“Be part of the high-altitude expeditions organized by Lakpa has been a beautiful experience – Khiru tells me. I decided to quit when my daughter was born. Working as a porter over 5,000 meters is too risky a job”. For example, on the Everest sherpas have to go up and down along the most dangerous sections of the climbing way, known as “the Khumbu ice-fall”, an ice-wall from which huge ice-blocks often fall. Tourists cross this climbing stretch as fast as possible. On the contrary, porters have to walk along it twenty times per expedition. The ones in charge of fixing security ropes and stairs on which clients will proceed – a task which could take the whole day working and killed too many of them – are called “Icefall doctors”.

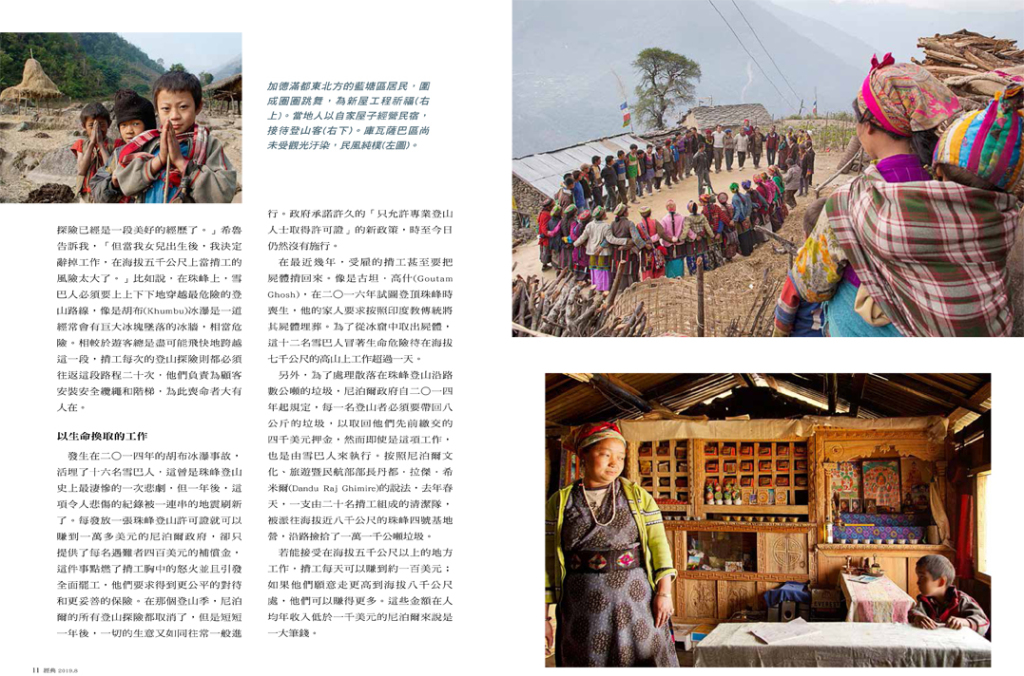

In 2014, the Khumbu ice-fall buried 16 sherpas in a single time, the worst tragedy in Everest climbing history (one year later, this sad record was overcome due to a series of earthquake that killed thousands of Nepali people, including 17 climbers buried under an avalanche at the Everest Base Camp). The Nepali government, which earns 11,000 dollar from each permit granted to Everest climbers, offered 400 dollar as indemnity for the victims. A measure which let the porters anger explode and brought to a general strike of the category, asking for a fair treatment and better insurance conditions. That season, every single mountain expedition in Nepal has been cancelled. But just one year later business started again as usual. The continuous promises made by the government about “a new policy” which will allow just expert climbers to get a permit, remain unaccomplished.

In recent years, porters have been employed even to take back death-bodies. Is the case of Goutam Ghosh, an Indian climber who died in 2016 trying to reach the Everest peak. His family asked to bury the body according with the hindu religious tradition. Taking the corpse out of the ice took more than one day working at 7,000 meters altitude. A mission in which 12 sherpas risked their own lives.

To tackle the tons of garbage littered along the Everest climbing way, since 2014 Nepali government has established that every climber has to take down to valley 8 kilos garbage (in order to get back the 4,000 dollar deposit they were requested to pay). However, even this task is carried out by sherpas. According with Dandu Raj Ghimire, director general of the Nepali Department of Tourism, last Spring a clean-up team of 20 porters has been sent up to Everest Base Camps 4 (7,950 meter altitude) where it collected 11,000 tons garbage on his way down.

Accepting to work over 5,000 meters altitude, porters can earn around 100 dollars per day. Even more if they are ready to go further and face 8,000 meters. A lot of money in Nepal, where the annual income per capita is less than 1,000 dollars. Khiru has a family, a schooling and a number of economic alternatives to explore. Many other porters don’t have his luck. Those who have former experience on the Everest climbing can aim at working as guides, earning as much as 5,000 dollar to bring an expedition on the mountain peak. Enough money to buy an house in their villages. A perspective which every year moves more porters to risk their lives. Season after season.

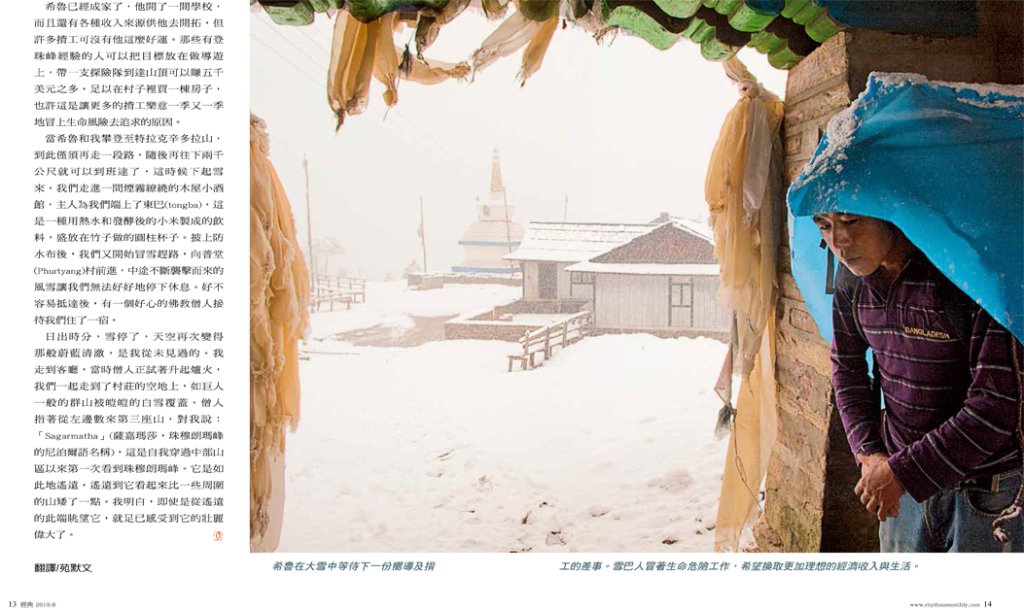

While Khiru and me are climbing to the Traksindo La – next to last Pass before the 2,000 meters down-hill to Bhandar – it starts snowing. We stop in a smoky tavern made of wood, where the host offer us tongba, a beverage made of hot water and fermented millet served in a bamboo cylinder provided with a straw. Protected under waxed sheets, we take back the footpath under the snow. But after walking a couple of hours, when we try to have rest, frost descends upon us. We move again to reach Phurtyang village, where a kind buddhist monk hosts us for the night. At sunrise snow falling is over and the sky is a kind of blue I never saw before. I move down to the living room, where the monk is trying to fire up the stove again, and we go out together on the village terrace. In front of us, a great wall of giants covered with snow. The monk points his finger to the third mountain from the left and says, “Sagarmatha”. It’s the first time I can see the Everest since I started my journey through the Middle Hills. It’s so far that the perspective let it looks lower than some of the mountains around it. But it’s enough to look at it from here to feel its greatness.