Little more than 10 years ago, Ziway was a small fishermen village in the Rift Valley, 160 km south of Addis Ababa. Marabus and pelicans would stroll undisturbed along the Vulcan lake shores, where they would also find plenty of food from the offals left around by fish cleaners. Along with fishing, small patches of greengrocery-cultivated land on the lake shores ensured livelihood to local population. One day of 2006 a man arrived in the village who would have changed the destinies of the site. John Barnhoorn, the son of Sher’s founder and present Executive Director of the Dutch company leader in the worldwide rose business, had come to inspect the land that the Ethiopian authorities were offering them to set up their greenhouses. John is a big man with a serious expression. His ice-blue eyes and snow-white skin make him look very exotic at this latitude. One can well imagine how he may have then captivated Ziway’s villagers while he was tasting the soil and having his expert sight slide over the lake shores.

Since then industrial floriculture in Ethiopia has experienced a dramatic growth. According to the Ethiopian Horticulture Producer Exporters Association, in 2019 the sector was worth more than 300 million dollars (as compared to 12 million in 2007) and makes up 10 percent of Ethiopia’s exports, ranking third behind coffee and leather. Prior to Barnhoorn family’s arrival Ethiopia did not export one single rose, today it is among the four biggest global producers along with Colombia, Kenya and Ecuador. In the need for globally traded currencies – foreign investment regulations include depositing hard currency with Ethiopian banks, which the investor then converts within a month into the local currency, the birr – the Ethiopian government has granted flowers investors exceptional conditions: free land exploitation, zero import duties on equipment and other production means, no taxes on profits in the first five years operation. But indeed the reason for Ethiopia becoming in little more than 10 years the new floricultural Eldorado is the very low cost of manpower: the average monthly wage of people working in the greenhouses is less than 30 dollars.

At present in Ethiopia there are 72 active flower farms, which occupy more than 2thousand hectares of land. Ethiopian government aims to boosting foreign-exchange earnings from flowers to more than one billion US dollars a year. In order to achieve that goal, the government plans to release a further 6,100 hectares of land dedicated to floriculture. As Ethiopia’s floral industry blossoms, according to reports from the Amhara National Regional State Disaster Prevention and Food Security Program Coordination Office every year 3thousand people are displaced by investors that acquire land to establish flower farms. The Land Matrix database, compiling data on land grabs from Governments, companies, NGOs, the media and citizen contributions, has tracked about 1.4 million hectares of land grabbed in Ethiopia in recent decades. Millions of Ethiopians have lost their land to investors, targeting production of flowers and other non-traditional agricultural exports.

Around one third of the roses sold on the European market – almost 100million just on Valentine’s Day – comes from Ethiopia. Recently Ethiopian flower-growing industry is looking at the United States in a bid to break the dominance of Latin American producers in supplying roses and other blooms to the world’s largest economy. State-owned Ethiopian Airlines Enterprise currently transports stems there only in the bellies of passenger jets. But the company is evaluating freighter flights through Miami (the main entry point for U.S. flower imports) Los Angeles or New York. What encourage flower exports to the United States is the African Growth and Opportunity Act, a U.S. Trade Act intended to enhance market access for Sub-Saharan African countries, allowing local producers to export tax-free to the United States. Profiting of the same agreement, many textile manufacturing companies – mostly Chinese, but even the U.S. textile giant PVH owning labels as Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfigher – are relocating their productions to the new Ethiopian Industrial Parks – already operating in Hawassa, Kombolcha, Addis Ababa, Mekelle, Adama, Jimma, Dire Dawa, Bahir Dar, they should be as many as thirty by 2025 – transforming Ethiopia in a new global hub for textile and manufacturing.

Only in Ziway, Sher industrial floriculture pioneers have set up 40 greenhouses over 700 hectares. The small greengrocery-cultivated patches of land have thus been replaced by an endless stretch of whitish greenhouses which from the surrounding hills look somewhat like a sickly prosecution of the lake. Therein work 13,000 people, approximately 70 per cent of which are women. A sleepy small fishermen village has been transformed into a frenetic townlet capable of drawing thousands of people from the surrounding countryside.

A cart driven by two buddies drops me in front of Sheer Ethiopia’s main entrance. Despite it’s Sunday the street renamed by local people “Flowers Avenue” is bustling. People come and go by feet or bicycle, workers from nearby villages huddle in the truck trailers. John is back home in the Netherlands for Christmas, but before leaving he has fixed an appointment for me with Kebel, the person in charge of public relations. His office is in Hall 11, about 2,000 meters away from the main entrance. On my way there I have a chance to take a first look around. Every hall is garrisoned by two fierce-looking armed guardsmen. With a little luck I succeed in getting into Hall 3. Inside it is very hot and you can hardly breathe, therefore no one of the employees – mostly young women – is wearing the coverall and masks necessary to be protected against pesticides and chemical fertilizers that saturate the air. Gloves are worn only by women assigned to stem cutting.

I reach the meeting place half hour late. While moving to visit the Hall 11 Kebel explains to me that an “integrated” approach is applied to fight parasites in the greenhouses, using both natural and chemical substances. As indicated on a board hanging at the Hall’s entrance, these roses were planted in 2007: every 15 days they provide new buds ready for the market. Just in the Ziway plant Sher produces daily 5 million rosebuds, 95 per cent of which is already sold on order.

From the conservatory we pass on to the parceling department. Here roses are divided according to stem length and packaged in bunches ready for shipment. Rose bunches are then placed in big paperboard cases which will be kept in refrigerators prior to being air shipped to Amsterdam, the main world distribution market. From there they will be shipped to final destination markets in Europe, Americas, India, Russia, etc.

Despite the fact that production has been moved to world’s Southern countries, the Netherlands remain leader in global floriculture. From production input (seeds and cultivars, pesticides, fertilizers) to final marketing, Dutch companies and capitals are absolute market leaders. Royal Flora Holland manages the largest flower market in the world: in 2018 this cooperative traded about 2,5bilions euro of flowers (mostly roses) and 4,6bilions including other plants. The daily turnover in Aalsmeer auction totals over 10million euros. 90 per cent of roses produced in Ziway and in other Ethiopian flower plants are shipped on air-cargos to Aalsmeer, where they compete with blossoms from 64 other countries. At Flora Holland headquarter, which covers an area equivalent to 182 soccer fields, workers standing on electric carts and wearing reflective safety vests move trolleys with flowers around the warehouse. Alongside the auction floor, several dozen traders, many of them graying, middle-aged men, sit in an auditorium that seats 300 people, facing auction clocks on the wall. All wear headsets to communicate with the auctioneers seated opposite each other in the bottom corners on the bidding hall’s floor and in other salesrooms.

The Dutch government has ceased gas consumption subventions and increased salary taxes in the floriculture sector, thus causing flower production decrease by 65 percent in the latest years. But this disincentivation policy at home is exactly the reverse abroad. In Ethiopia Dutch Cooperation is among the major stakeholders of floriculture booming. Among other initiatives, organizes and finances Addis Ababa’s Hortiflora Expo – latest edition in March 2019 – where all East Africa sector operators meet. Many companies, such is Sher’s case, are implementing so called turnkey projects: set up the greenhouses, organize production and in 10 years maximum sell the whole plants to another company. As shown by “Endogenisation or enclave formation? The development of the Ethiopian cut flower industry” (Cambridge University Press, 2010), “the Dutch are building a sustainable, high-quality, supply base for their world-leading flower auctions”.

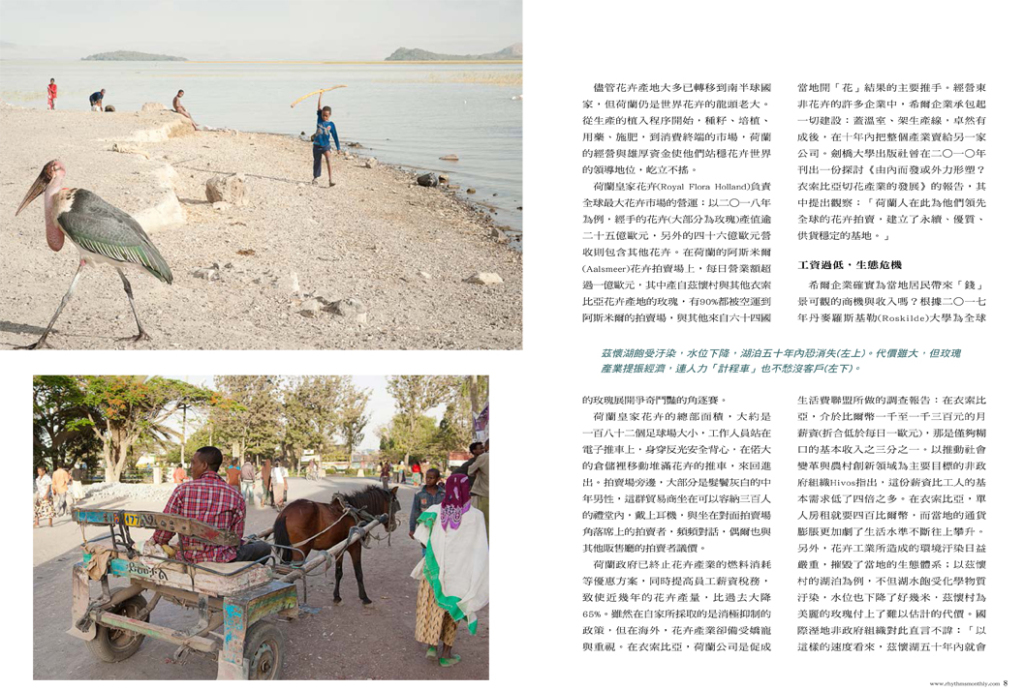

But Sher arrival has been a good business for local people as well? According to a 2017 Roskilde University’s study for the Global Living Wage Coalition, monthly wage ranges from 1,000 to 1,300 birr (less than 1 Euro a day) which corresponds to one third of local subsistence income as estimated by researchers. According to Hivos Ngo wages would be four times lower than the amount needed to cope with basic needs (the average cost of a leased room is 400 birr while strong inflation makes cost-of-leaving in Ethiopia steadily rise). The heavy pollution due to industrial floriculture is causing serious damages to the local ecosystem. The level of Ziway lake has dropped by some meters and its waters have been contaminated by chemical substances. According to Wetlands International Ngo’s researchers “by this pace Ziway lake is doomed to disappear within 50 years. Local population which used to drink the lake’s water after just minimal treatments must now pump drinkable water from a source almost 50 km faraway. Purifying the local resource has become too complicated and expensive”.

In Ziway Sher has built a school and a hospital that are both free for workers’ families. The Barnhoorn have also built a Police station and a Court of Justice. Such tasks should normally be performed by the local government, which would easily provide for such works if only it could rely on the payment of fair fiscal duties by the Dutch company. But the Barnhoorn, while collecting money on the international market – Kkr, one of the major European investment funds, has bought Sher-Ethiopia shares for a value of 200 million dollars – using complicated fiscal tricks report low profits to Ethiopian Revenue thus paying derisory taxes. Among the tricks used to wriggle out of Ethiopian Revenue, Sher-Ethiopia borrows money from the Dutch branch office at an interest rate (9 per cent) higher than market rate, while the AfriFlora brand is entered each year as a cost.

While visiting Sher-Ziway parceling department, on the roses’ covering I am surprised to notice the Fairtrade label. Kebel informs me that, besides Fairtrade International, Sher’s roses claim as well Ethical Trading Initiative labels. I wonder how can trade be considered fair when people are paid less than one dollar a day to work in an unhealthy workplace. Or ethical when it misappropriates land and water destined to agricultural production in a country repeatedly hit by famines to produce flowers to be sold to consumers in rich countries.

In order to cope with critics, Fairtrade International decided to reconsider its Ethiopian standards. Up until 2017, to obtain a Fairtrade certificate employees were required to pay their workers at least the national minimum wage. But in Ethiopia, where this doesn’t exist, companies were able to decide what they paid their employees. Recognizing this as a major problem, in 2017 Fairtrade International introduced a new requirement. Now, companies must implement a plan to work towards applying wages that correspond with the World Bank’s global poverty line (1,90 dollar per day, approximately 2thousand birr per month). However, according to Caroline Wildeman, coordinator of Women@Work – a campaign led by Dutch NGO, Hivos, which aims to improve conditions for women working in global horticulture supply chains – due to the lack of a deadline on this regulation, no flowers currently on the Dutch market have been produced at this wage. Still, movements towards positive change are being made: in July 2019, the Dutch floriculture sector (including Sher) signed a new set of guidelines, formed together with the government, the trade union and Hivos. The multi-stakeholder agreement requires the Dutch sector to work towards a more sustainable supply chain and by April 2020 all flower exporting farms have agreed to pay wages that correspond to the Ethiopian living wage of 1.75 euro a day. “They have put their signature on it, but there has been a lot of resistance because currently, no one pays that much”, Wildeman points out. “You cannot say that it’s all negative, but in general, the wages are still low, and other conditions, in regards to protection from harmful chemicals and health and safety issues, still need to be addressed”.