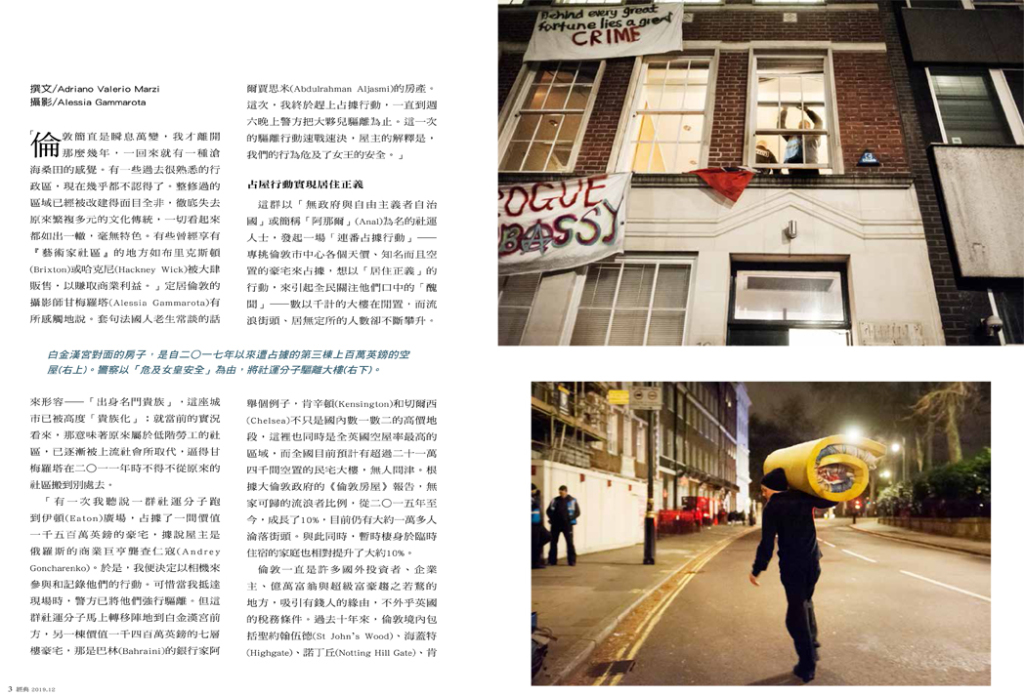

“London is changing so fast that just living abroad for a couple of years has been enough to make me feel lost when I was back. Some of the boroughs I was familiar with have become unrecognizable with a bang. The renovated areas are flattened out, lost their cultural richness, look self-same. Place like Brixton or Hackney Wick are now sold on the market taking advantage out of their historical connotation, ‘the artists neighborhood’, even if the artistic community who inhabited the area has totally gone missing”. Alessia Gammarota is an Italian photographer living in London, where the gentrification – from the old French genterise, meaning “of gentle birth”, currently referred to the displacing of lower-class workers by upper-class people – forced her to move from a neighborhood to the other since 2011. “Once I learned about a group of activists occupying an empty £15million mansion in Eaton Square, owned by the Russian oligarch Andrey Goncharenko – Gammarota tells – so I decided to join them with my camera. When I got there police had already forced them out. But immediately after they occupied a £14million seven-storey mansion in front of Buckingham Palace, owned by Bahraini banker Abdulrahman Aljasmi. This time I was with them when police came on a Saturday night to throw us out. The eviction was fast-tracked cause according to the owner we were putting the queen’s security at risk”.

Known as Autonomous Nation of Anarchist Libertarians, or Anal, those activists were involved in a “rolling programme” to occupy high-value and high-profile buildings in central London to spotlight what they say is the scandal of thousands of empty buildings while the number of homeless people and rough sleepers is on the rise. Despite being the richest borough in the country, Kensington and Chelsea have the highest number of empty buildings in the UK (over 214thousands empty residential buildings are currently estimated in the whole country). According to the Greater London Authority’s “Housing in London” report, homelessness in the capital increased by more than 10% since 2015, while around 10thousands people are now estimated to be sleeping in the streets. Likewise, the number of families living in temporary accommodations grew by approx. 10% in the same period.

London is the destination of choice for foreign investors and oligarchs, billionaires and super-rich people, appealed by the favorable tax environment in UK. Entire neighborhoods – St John’s Wood, Highgate, Hampstead, Notting Hill Gate, Kensington – have undergone a major change in the past decade. Estate agents refer to these centrally located “super prime” areas as “golden postcodes”. They have long been wealthy places, but in the past, like most of London, they were also mixed. Now ultra-high-net-worth individuals have displaced even wealthy people from Kensington. They in turn are displacing others to suburban areas, creating a domino effect that ripples through the city, with the consequence for average-income earners and the poor to be pushed to the periphery or out of the capital.

Wealthy people are encouraged to use property as a profitable financial asset and the rising rents are forcing out low-incomes: 30 percent of London households now have to find a home on the private rental market controlled by estate agents like Foxtons – “Britain’s most hated property agent”, because of its aggressive tactics and leading role in the gentrification of Inner-London neighborhoods – and across London rents have risen to an average of £1,588 per month, 70 per cent higher than the UK average. People who do not earn enough to meet those extortionate rents are leaving the capital: the vacancy rate for nurses at London’s hospitals is 14-18% and the number of entrants to teacher training has fallen 16% since 2010.

Moreover, London’s skyline is undergoing a thorough transformation as consequence of an unprecedented wave of new constructions, featuring plans for 300 new luxury residential towers. From Nine Elms up to Vauxhall and along to Southwark and Blackfriars bridges, mile upon mile of apartments in gated neighborhoods have already been built. At Elephant and Castle, in the central Zone 2, the Australian property developer Lendlease is working with Southwark council to render the area unrecognizable, replacing the affordable housing that once characterized it – just in Heygate estate, over thousand popular houses have been completely demolished and cleansed – with a forest of gleaming towers.

A new development on the south bank of River Thames, properties on Southbank Place, start at £1million and go up to £7.85million. According to a report by Transparency International, 40 per cent of the apartments were bought by offshore companies registered in British Virgin Islands tax haven and 60 per cent by investors from high corruption risk jurisdiction. In the decade between 2005 and 2014, at least £170billion worth UK property was acquired by offshore companies registered in tax havens. Transparency International has been unable to identify the real owners of more than half of the 44thousands UK land titles registered to overseas companies, but 9 out of 10 of the properties were purchased through tax havens.

That’s the same environment in which, in June 2017, Grenfell Tower fire killed 72 people – the deadliest fire in Britain in more than a century – cause of a flammable cladding which was added to reduce the negative esthetic impact of the council estate on the wealthiest borough in the UK. Kensington and Chelsea Tenants Management Organization, the quasi-governmental owner of the building, totally ignored residents’ complaints about the safety risk connected with a cladding made of a combustible core of polyethylene sandwiched between two sheets of aluminum. This kind of flammable cladding is forbidden in the United States and in many European countries on every building higher than the firefighters’ ladders. Not in the UK, where over 300 residential blocks are still coated with flammable cladding similar to that installed on Grenfell Tower. Though thousands of people from the local community and across London protested for weeks in front of Kensington and Chelsea town halls demanding justice, so far not a single contractor, councilor, consultant, member of Parliament responsible at various levels for the disaster has yet been arrested. Families and friends who mourn the victims have waited 2 years and 4 months for the first findings of the public inquiry, published on October 30th. According to the report, not only did the panels on Grenfell Tower fail to resist the fire but they “actively promoted it”. The failure of fire doors, for which Kensington and Chelsea council and its Tmo were responsible, is also identified as a cause of the rapid spread of the fire and smoke inside the building. However, most of the document contains strong criticisms of the London fire brigade, even if it suffered of dramatic governmental budget cuts in recent time. So far, the Grenfell tower inquiry has cost the taxpayer at least £40millions, more than 100 times the savings made by swapping fire-retardant cladding on the council block for cheaper combustible panels that fuelled the fatal fire.

Throughout the 20th century public housing has accounted for a major part of British accommodation. Since the 1980s, public housing stocks have been steadily eroded due to the combination of Margaret Thatcher’s right-to-buy policy, which brought about the sell-off of 2millions council homes, and buy-to-let, which resulted in 40 per cent of those former council homes now being owned by private landlords, who rent them out at 3 and 4 times the price that council tenants pay for the remaining local-authority-owned properties.

In the last 20 years, council housing has been targeted by politicians as the failure of the State. In January 2016, David Cameron wrote in the Sunday Times: “Some of them, especially those built just after the war, are actually entrenching poverty. On these so-called sink estates you’re confronted by concrete slabs dropped from on high, brutal high-rise towers and dark alleyways that are a gift to criminals and drug dealers”. The former Prime Minister announced a scheme to identify the hundred estates most “ripe for redevelopment”. “For some, this will simply mean knocking them down and starting again”, he concluded.

In 1997, Tony Blair chose the “forgotten people” of the Aylesbury – completed in 1977, three years after the Grenfell Tower in the same architectural style known as Brutalism, Aylesbury is one of the largest housing complexes in Western Europe with 2758 flats that were home to around 7500 people – and similar estates as topic of his first set-piece speech as premier. Generalizing about council housing in almost exactly the same terms that Cameron would employ 19 years later, Blair warned: “There are estates where the biggest employer is the drugs industry, where all that is left of the high hopes of the postwar planners is derelict concrete”.

In 2017, Architects for Social Housing (Ash), an association which uses confrontational tactics to defend estates and attack their regenerators, produced a map of London’s estate regeneration programme. They identified 237 council or housing association estates that have recently undergone, are currently undergoing, or are threatened with demolition, privatization or renovation resulting in the mass loss of homes for social rent and the social cleansing of existing residents from their communities. According with Paul Watt, a reader in urban studies at Birkbeck college in London: “As many as 90 council estates are potentially facing demolition in London. Even if most of these are much smaller than the Aylesbury, this could mean the disappearance of anywhere between 20thousands and 200thousands council homes”. By demolishing the only form of housing that offers an alternative to the market, and by clearing inner-city land for redevelopment as investments for global capital, the estate regeneration programme is the driving mechanism of London’s housing crisis, affecting not just the 24 per cent of Londoners who still live in social housing.

Aysen Dennis is a Turkish refugee, who has been living at Aylesbury estate as a council tenant since 1993: “For the first time I feel safe and to belong to somewhere. Most of the inhabitants of Aylesbury are people in my same situation: part of a minority, outsider of the society. But here we form a strong and brilliant community, which has to be protected”. In 1998, shortly after Blair’s first visit, Southwark’s council was promised £56millions government funding to help transform the Aylesbury. The plan was to knock down most of the estate and build a new settlement, including thousand extra dwellings, which would be sold to private buyers in order to raise additional funding. Meanwhile, ownership and management of the rental properties would be transferred from the council to a housing association. In 2001, however, 73 per cent of residents on a 76 per cent turn-out voted against the council’s attempt. But in 2005, Southwark declared that Aylesbury would be demolished, regardless of the ballot.

Since then the estate have been gradually emptied and demolished by the council. Notting Hill Genesis is the housing association in charge of “regenerating” the Aylesbury in more than 4 thousands new properties. Just 1300 of them will be for social rent, less than half as many council home as the estate originally provided. This happening in a borough with 11thousands households on the council housing waiting list.

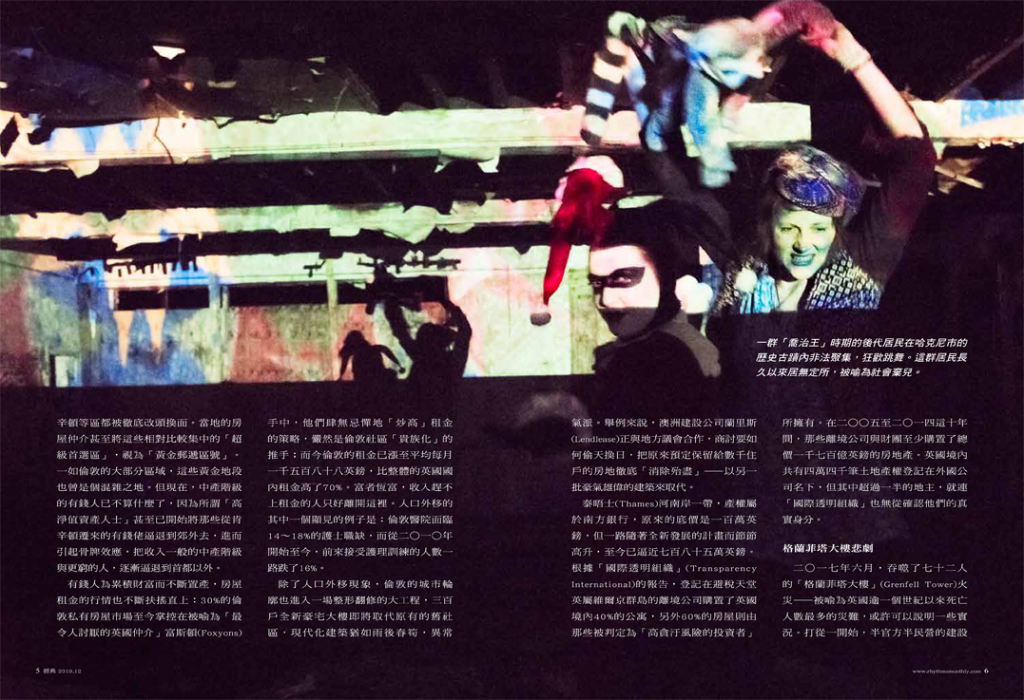

In January 2015 a march of a few hundred protesters through Southwark to defend council housing turned into an invasion of some of the Aylesbury emptied blocks. The estate remain occupied by squatters and campaigners for over two months. Council responded by sending riot police and putting a fence around the blocks manned by private security guards. The court finally evicted the occupiers, but the wall was left up. The remaining residents are still living behind it, accessing their homes through security guards armed with dogs. Council refusing to do any repairs to their homes.

“Aylesbury is in the very central zone 1, next to a big park, just two miles from the Houses of Parliament. Council doesn’t like working-class people occupying such a valuable land. That’s why they want to kick us out and make room for rich people”, Dennis tells. Some hundreds of the last residents are leaseholders, who had previously bought their homes from the council under the right-to-buy policy. But now they are facing their compulsory purchase, for a price set by the council. Details of the amounts paid by Southwark for these homes were obtained by campaigners under the Freedom of Information Act and show offers much lower than the market value. Local authorities, the government and the land tribunal have all backed an approach that has compensated leaseholders based on the average value of homes on the estate to be demolished. It is obvious that this amount won’t be enough for leaseholders to afford a home in the area. So the council offer them to enter a shared ownership scheme: leaseholders are given the “opportunity” to buy back part of a home on the new estate with the money they have been given for the compulsory purchase, paying rent on the remaining share. For the big majority of residents these offers are simply unrealistic.

The campaigners to save the Aylesbury strongly disputed the compulsory purchasing scheme. In September 2016, to the surprise of everyone, the UK’s Secretary of State upheld the Government Inspector’s recommendation to stop it cause of its negative effects on the communities. However, in April 2017, following increased offers to leaseholders, the Secretary of State lifted his block. A year later, in April 2018, the majority of Aylesbury leaseholders withdrew their objections after reaching a confidential agreement with Southwark council.

“Cause of the agreement they made behind our back – Dennis tells – we lost the first part of the Aylesbury. But other leaseholders and the tenants like me are still fighting. Most of my original neighborhood moved out, which made me very sad. Just on my floor seven flats have been made empty by the council. In the borough lots of families are desperate to find a place to live in, but council keeps flats empty. Why this is happening? How is possible profit has to come before people? This makes me furious. Last 20 years I have been campaigning to resist. We have to make whatever is possible to stop the social cleansing of London working-class. I won’t move out until the very end”.