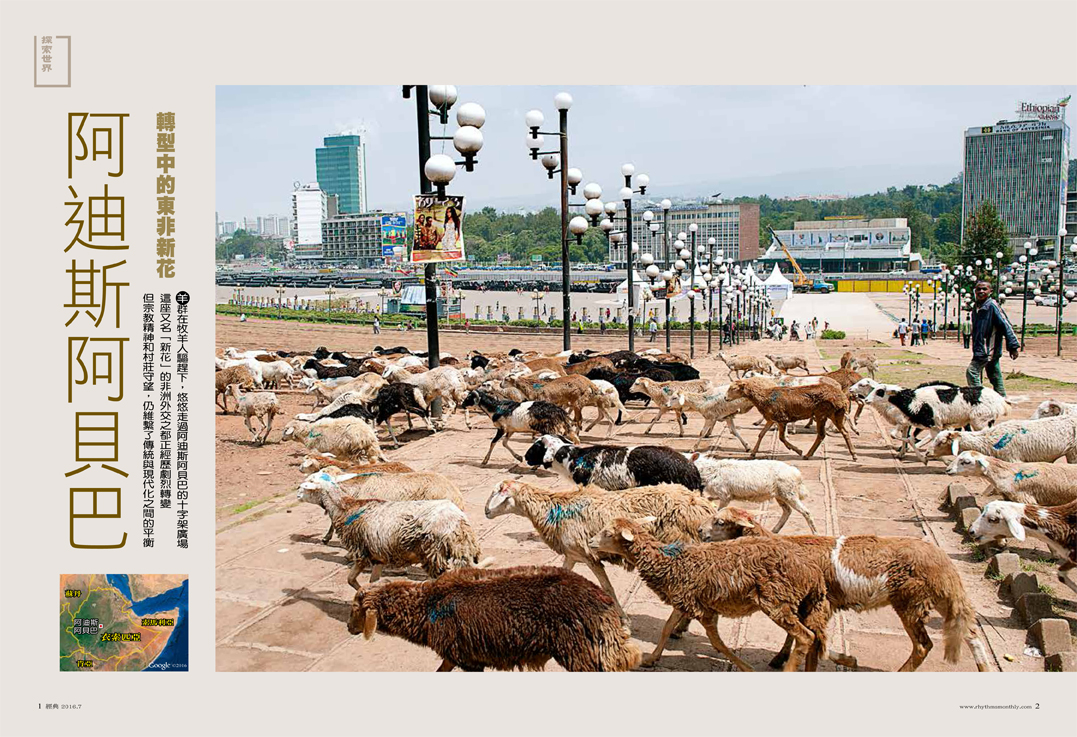

In the late Sixties and early Seventies of last century Addis Ababa was named “The Swinging City”. Those years’ western symbols – soul and funky music, the black singers James Brown and Sam Cooke, the hippie freedom philosophy and 1968’s cultural revolution – had reached Ethiopian highlands, but here were embraced according to the Ethiopian mood. Mahmoud Ahmed, Tilahun Gessesse, Alemayehu Eshete, as well as other young Ethiopian musicians, got off the stiffened uniforms of Haile Selassie’s “Imperial Body Guard Band” to wear fashion bell-bottoms, and left the ballrooms and theatres where they used to perform to spend their nights playing at Patrice Lumumba’s, the new trendy nightclub in Wube Braha working class district. Among spirits and miniskirt wearing girls, the new generation introduced the chasing rhythms coming from over the ocean on the pentatonic scales and into Abyssinian musical tradition pathos. A mix of sounds arose from there and thanks to the Ethiopiques series would in later years come off successfully all over the world.

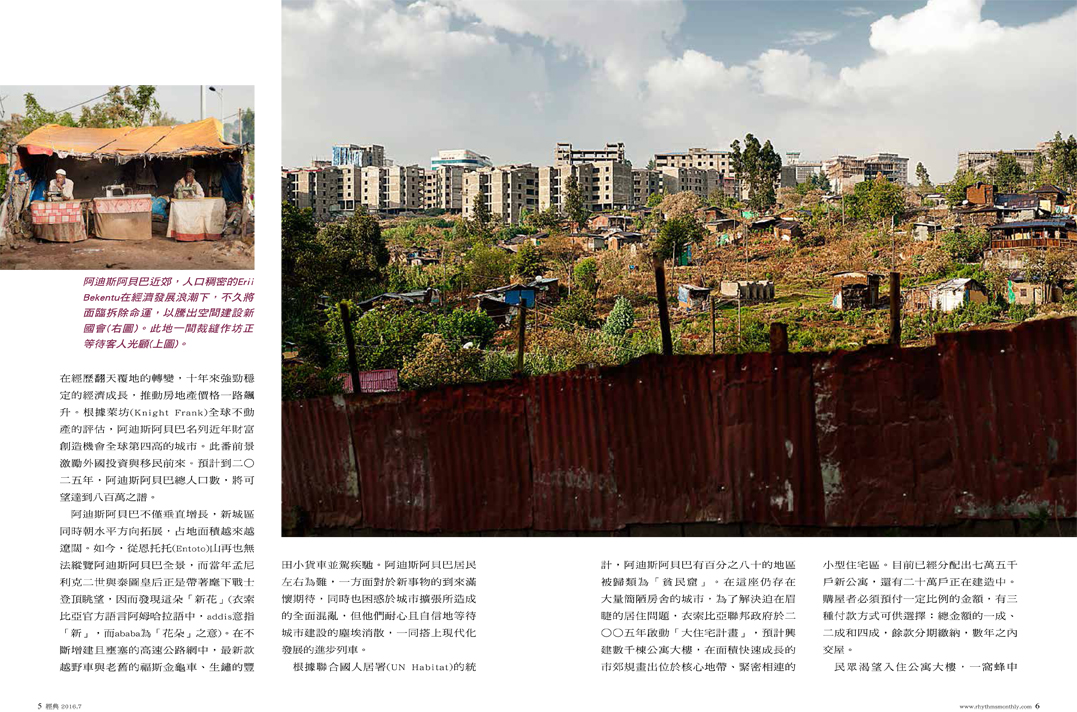

Nowadays at Patrice Lumumba’s spirits and girls are still to be found, but music is played just by an old jukebox, while the historical nightclub is under risk of being shut up. The “forest city” founded at the end of nineteenth century by Emperor Menelik II and his wife Itegue Taitu has developed to a modern “concrete jungle”. As new concrete-and-glass skyscrapers come up like mushrooms, the traditional neighborhoods made of wood and mud are blown down to make room for a new skyline worthy of a modern global capital. Wube Braha – “my wonderful desert” – is fated to follow Erii Bekentu’s destiny – “nobody will hear even your shouting” – as populous as notorious a neighborhood, of which scarcely some broken walls still stand. Along its borders doors, gates and whatever else has escaped Government’s bulldozers are on sale. On top of the esplanade the skeletons of the new condominiums overcome what is left of the old shanties. They will soon be ready to host Addis emerging class people.

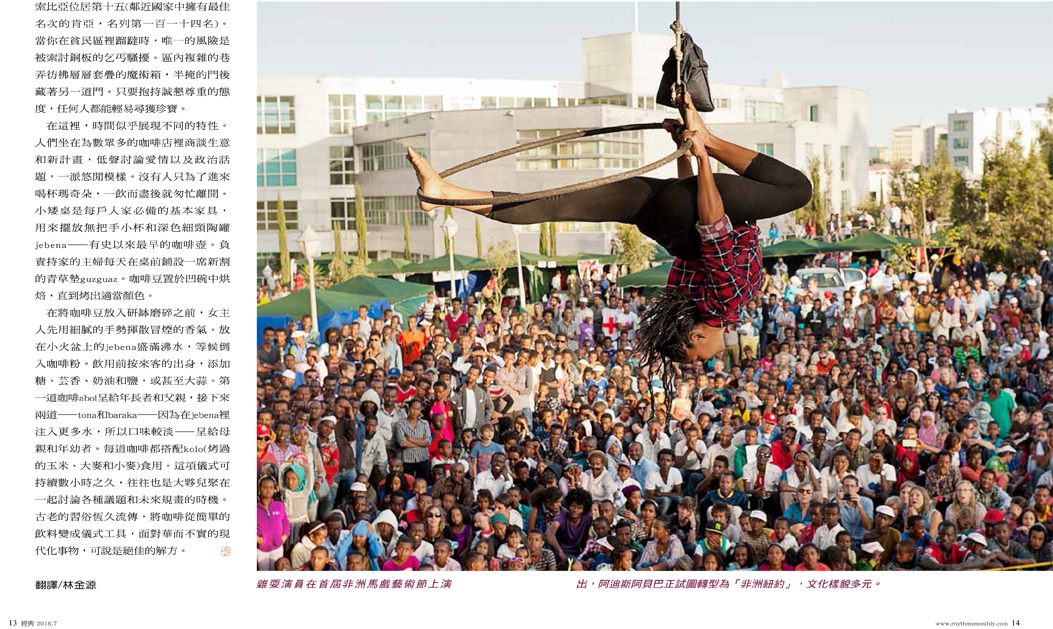

Included by New York Times and Lonely Planet in the list of the world’s top cities to visit, Africa’s diplomatic capital – Addis Ababa ranks third after New York and Geneva for number of diplomats, hosting the headquarters of the African Union, the UN and of the major development cooperation agencies operating in Africa – the city is experiencing an extraordinary transformation. Since a decade economic growth is strong and steady, while estates value is skyrocketing. According to “Knight Frank” Global Real Estate, Addis Ababa is among the top 4 cities in the world for wealth creating opportunities in the near future. A prospective which fosters both foreign investments and immigration: by 2025 Addis is expected to have a population of 8 million people, as compared to 3 million in 2010. The city’s growth is not just vertical, the new city is also stretching over a much larger surface. It is not even longer possible to have an overall view of Addis from Entoto, the hilltop from where Menelik II and Taitu descended with their warriors to found the “new flower” (in Amaric addis “new”, ababa “flower”). On the ever expanding and trafficked motorway network the latest models of cross-country vehicles hurtle next to old VW Beetles and rusty Toyota vans. Torn between great expectations from the “New” coming forth and bewilderment caused by the chaos growing all around, Addis’ inhabitants wait patiently and confidently for the dust of the city-yard to fade out and the train of modernity to allow them all get up.

In order to cope with the housing emergency in a city still covered extensively by shanty-towns – according to UN Habitat 80 percent of Addis is classified as “slums” – in 2005 the Ethiopian Federal Government launched the Grand Housing Program which foresees the building of thousands of condominiums – small blocks of buildings in central areas and compact arrays in the rapidly growing outskirts. 75,000 new flats have been already assigned to owners and 200,000 more are under construction. A certain percentage of the house price is to be paid in advance – three different options are provided: 10/90, 20/80 and 40/60 – while the remaining amount will be paid in instalments, delivery occurs in a number of years. A revolution called mortgage which is generating a new mass phenomenon: the hope for a life in a condominium. When the call for assigning new lots of apartment houses was launched long queues of people waited before bank agencies. A sudden increase of divorces occurred: each family was allowed to file just for one flat assignment, so many couples went in for divorce to double their chances. So long 450,000 applications have been filed, but only a small percentage of lower class families succeed in obtaining a loan due to a wage policy conceived rather to attract foreign capitals looking for cheap labor force than to promote the creation of a middle class capable of facing the jump to modernity. For those who can afford to comply with the requested advance payment, the promise of a bathroom not to share represents an epochal revolution. On the other hand many families risk to lose the little they possess and to be confined in a shanty-town tens of kilometers away from what has been the center of their life.

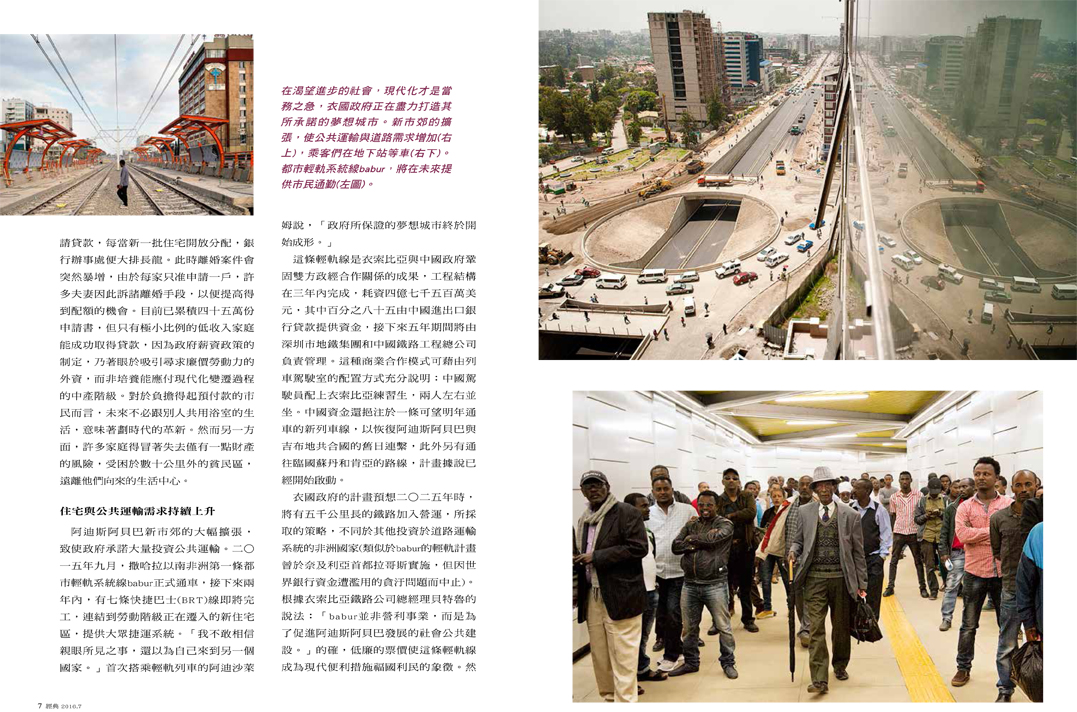

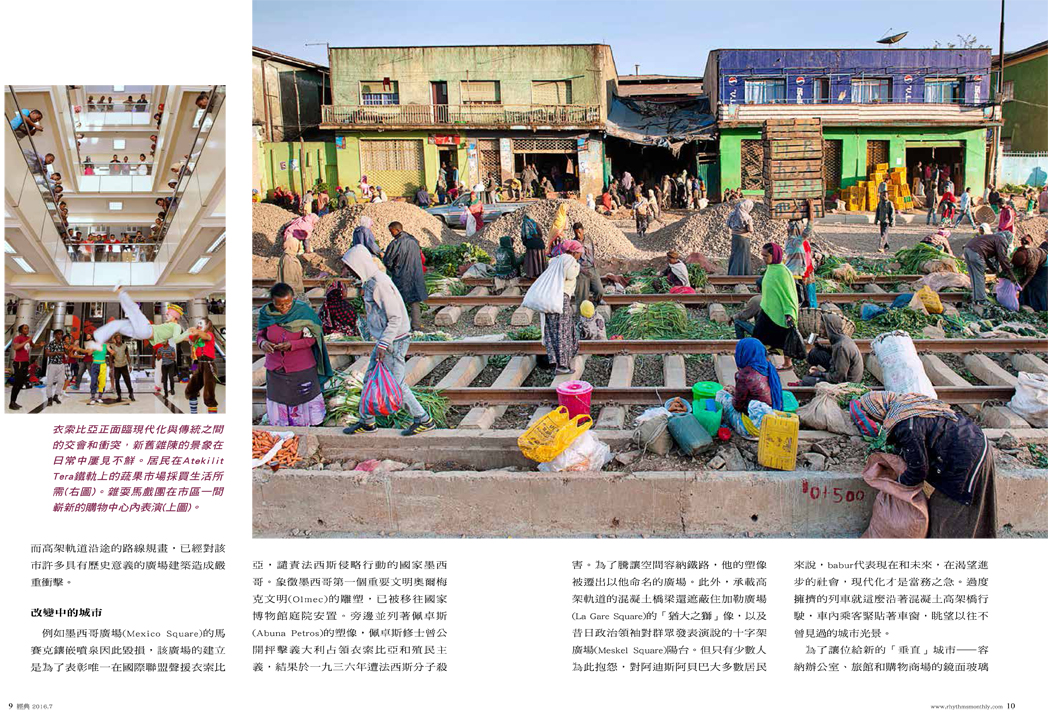

The huge expansion of the new Addis outskirts has originated the Government’s commitment to substantial investments in public transportation. In September 2015 the babur was inaugurated, the first urban light train in Sub-Saharan Africa, while in the next two years 7 Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) will be implemented to provide a rapid mass connection to the new districts where the working class is moving to. “I couldn’t believe what I was seeing, I thought I was in another country” says Addisalem after his first trip on the babur. “At last the city we were promised and we dreamed of is starting to be realized”. The train is the outcome of the consolidated political-trade partnership between the Ethiopian and the Chinese governments. The structure was completed in 3 years and cost 475 million US dollars, 85 per cent of which was financed by an Export-Import Bank of China loan, while over the next 5 years Shenzhen Metro Group and China Railway Engineering Corporation will be in charge of management. The best representation of this business marriage is to be seen in the train’s driving cab, where a Chinese driver and an Ethiopian trainee are seated side by side. Chinese capitals are financing also the new train line that is expected by next year to restore the historical Addis-Djibouti connection, while other lines bound to Sudan and Kenya are said to be already started up. Government’s plans envisage by 2025 5,000 kilometers railways to be put in operation, a strategy opposite to other African countries which are investing in road transportation (a light train project similar to the babur had been started up in Nigeria’s capital Lagos but corruption stopped it by World Bank’s funds misusing). According to the General Manager of Ethiopian Railways Corporation, Getachew Betru- “the babur is not a profit enterprise but a social infrastructure intended to foster Addis Ababa’s development”. Actually ticket fares are low, thus making the light train a symbol of modernity within reach of everybody. The layout for the new aerial railway has impacted heavily on many Addis historical squares. In Mexico Square the mosaic fountain was destroyed which was erected as a recognition symbol to the only one country which supported Ethiopia’s denouncing the Fascist occupation before the Nations’ League. The statue representing Olmec, the first major civilization in Mexico, has been moved to National Museum’s yard. Next to it is Abuna Petros’ statue, a priest murdered by Fascists in 1936 for having publically reprobated occupation and colonialism, removed from the homonym square to make room for the railway. The concrete bridges on which the aerial tracks run hide Judah’s Lion in La Gare Square, as well as the balcony in Meskel Square from where political leaders used to address the crowd. But just a few are complaining, to the eyes of the majority of Addis’ inhabitants the babur represents the present and the future, modernity coming forward in a society longing for progress. On the overcrowded trains running along the concrete bridges passengers glue to the windows looking out at a never seen before city’s view.

In order to make room for the new “vertical” city – mirror-glass skyscrapers hosting offices, hotels and shopping malls, but also concrete skeletons and awkward empty high-rises – government is tearing down the old sefer. These Addis’ most ancient popular neighborhoods are built up areas consisting mainly of low wood and soil cots built around a small courtyard, with a water pipe and a latrine in common; here and there some fine Italian or Indian style stone buildings appear (historical immigrant communities as Armenians, Turks and Greeks). Small villages coated during the raining season by slick mud, where water and power supply is precarious and sewage is not at all supplied. On the other hand they are places where social link is very strong due to a consolidated system of gorabet (neighborhood) relationships and informal economy. To overcome the impossibility to turn to traditional credit market, the sefer people have developed alternative financial methods, such as the Idir and the Ikub: the former is similar to a neighborhood common cash used to support weddings and funerals, the latter provides money for small investments. Every day, along the narrow gravel roads people left out of the Ethiopian economic boom spread multicolored napkins on which they arrange garlic and onions mounds, cabbage, dusty tomatoes and avocados pyramids. Here and there are blacksmith, carpenter and tailor shops, suk and all kind of street markets, coal stores – still the most commonly used cooking fuel -, mills where people get ground berberè – a spice mix that matches almost with all wot (sauces) – and teff flour – a high quality grain growing only on Ethiopian plateaus, used to prepare the enjera, a spongy crepe-like bread which is the basic food in all families. From the open doors comes the aroma of freshly roasted coffee beans spreading out into the air like a blessing.

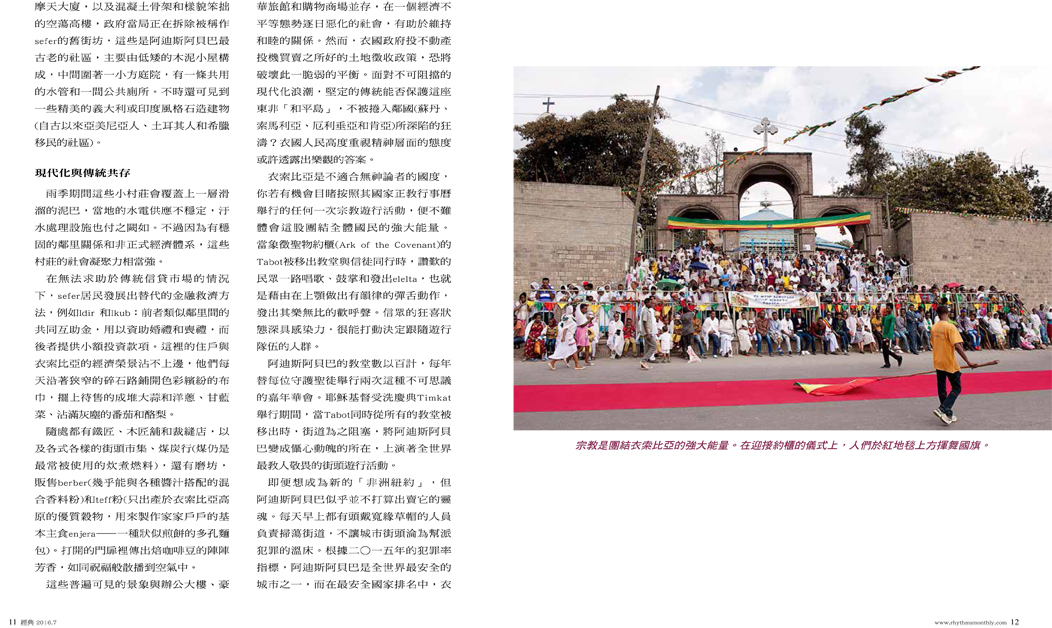

Coexistence of these popular situations with office buildings, luxury hotels and shopping malls puts rich and poor people side by side, contributing to guarantee social peace in a society where economic inequalities increase constantly. The expropriation policy pursued by the Government to free the areas quested after by real estate speculation risks to spoil this fragile equilibrium. Confronted by an overwhelming modernity, will strong Ethiopian traditions be capable of protecting the East African “Peacefull Island” from the violent spiral which is absorbing the neighboring countries (Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea, Kenya)? A positive answer may be found in the highly spiritual attitude of Ethiopians. Ethiopia is not a country for godless. Anyone who has a chance to witness any religious procession on the National Orthodox Church’s calendar can perceive the extraordinary energy that holds these people together. When the Tabot symbolizing the Ark of the Covenant – Moses’ Tables of the Law – leaves the churches to be taken among the believers, acclaiming crowds go along singing, clapping hands, raising elelta, i.e. emitting matchless bliss cries by means of a rhythmic hopping movement of the tongue on the palate. A contagious rapture captivates those who decide to follow the processions. In Addis these mystic street Carnivals are held twice a year for every Guardian Saints of hundreds churches. On the Timkat – Jesus Christ’s baptism celebration – streets are blockaded while Tabots move simultaneously from all the sanctuaries, transforming the City in the throbbing scenery of the most awesome street parade in the world.

To become the new “Africa’s New York” Addis doesn’t however seem to be ready to sell its soul. Swept up every morning by an army of operators wearing but straw wide-brim hats, the city streets are not criminal bands’ hunt. According to Crime Index 2015, Addis is one of the safest cities in the world, while Ethiopia ranks 15th in the countries list (Kenya, which has the best ranking out of the neighboring countries, is 114th). When strolling along downtown shanty-towns the only risk one can run is being annoyed by beggars pleading for a coin. These alleys resemble a magic boxes system, half-shut doors hiding another door. A treasure easily to be found by anyone showing cordiality and respect.

Here time seems to have a different dimension. Sitting at the tables of the many cafés people discuss of business and new plans, whisper about love and politics. With no haste. Nobody comes in just to ask for a macchiato, swallow it up and run away. Among the basic furniture pieces in each home there is a low small table on which stand small cups without handle and a dark clay narrow-necked jug, the jebena, the first coffee-pot in history. Every day the housewife lays before the table a bed of fresh cut grass, the guzguaz. Coffee beans are toasted in a concave bowl as long as they reach the due coloring. Before crushing them in the mortar, she spreads their smoking fragrance with delicate gestures. The jebena filled up with boiling water lies on a small brazier waiting for the coffee powder to be poured into it. Sugar or rue can be added before serving the drink, or butter and salt, or even garlic, according to the hosts’ region of origin. The first round, abol, is for seniors and fathers; the next two – tona and baraka – less strong since more water has been added in the jebena – are for mothers and younger people. Every round is accompanied by kolo (toasted corn, barley and wheat). This ceremony can go on for hours and is often an occasion for talking about several kind of issues and making plans for the future together. An ancient custom but always alive, which makes coffee turn from a simple drink into a liturgical tool. A great cure for forked tongue modernity.